Cities have spent three decades criminalizing homelessness. Last year, Austin bucked the trend—and sparked a firestorm that still hasn’t gone out.

By Gus Bova

September 21, 2020

The years living on the street showed in Alvin Sanderson’s weatherworn face as he approached the microphone at Austin City Hall last June. His bleach-white hair combed neatly back, the 64-year-old had come to urge the city council to roll back a 23-year-old ordinance criminalizing camping in public places, a law he said forced homeless Austinites into dangerous places like creek beds. He spoke of Suzie, a friend he said had been sleeping in a tunnel when a flash flood took her life. “She was a good person,” he said, his halting voice rising. “She surely didn’t have to die because of a camping ordinance.” He spoke of Sarah, a friend killed while resting in a dark corner of the city, and Doc, who drowned. The buzzer sounded—his allotted time was up—but he wasn’t through, squeezing in one more eulogy before returning to his seat. A row of activists arrayed along the hall’s back wall burst into applause.

Sanderson was the first of many to testify that night, most in favor of curtailing a trio of local laws that targeted homeless people. Just after 2 a.m., the council made its decision. Camping would now be allowed in many places in the city, including under highway overpasses; panhandling restrictions would be wiped from the books; and a ban on lying down, sitting, or sleeping in the downtown area would become, essentially, a ban on intentionally blocking sidewalks.

It was an unusual move. For three decades, cities nationwide have increasingly criminalized behaviors necessary for the homeless to survive, a law-and-order response to an unchecked affordable housing crisis. Other major Texas cities enforce suites of such laws, and Houston had passed a new camping ban just two years prior. Now Austin—Texas’ least affordable city—was going in the other direction.

In the months following the policy changes, as Sanderson predicted, homeless Austinites emerged from the woods or other hidden crannies of the city. Many moved to highway underpasses, which offer rain protection, visibility, and a regular breeze. Some who’d slept on cardboard and blankets now set up tents, obtaining a shred of privacy. “It was a lot of relief,” says Danny, a 51-year-old native Texan living under State Highway 71, when I visit him in July. “These folks are here because they’re scared of the woods. There’s snakes, there’s bugs. People have disabilities and can’t get around there.”

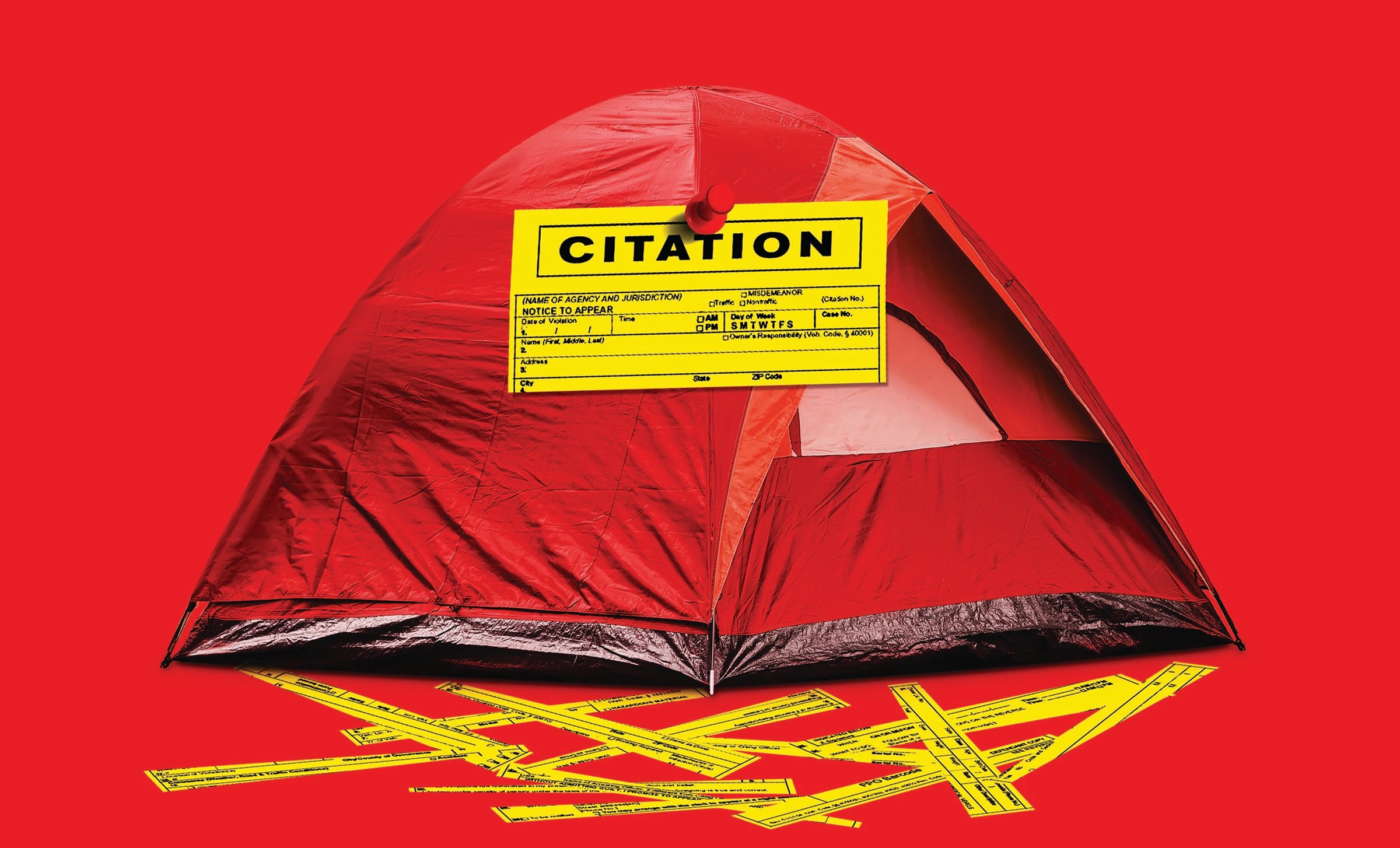

In making their case to city officials, advocates had also argued the ordinances perpetuated homelessness. Violating the bans could result in a Class C misdemeanor and a $500 fine. The vast majority of unhoused defendants failed to show for court, leading to warrants, arrests, and a criminal history that landlords can use to reject prospective tenants. “It’s a vicious cycle that just makes it harder to get into housing,” says Rachel Schuyler, 30, who currently lives under an overpass in North Austin and is starting a group called Hobos with God to help her fellow unhoused. Now, according to records obtained by the Observer, that cycle has been broken, as citations have all but evaporated over the past year.

But what came as relief for the unhoused also revealed something ugly within generally liberal Austin. For months, Governor Greg Abbott spread lies and misleading claims on Twitter, linking the city’s homeless with violence, filth, and general mayhem; local television stations sensationalized crimes committed by the unhoused and regurgitated anti-homeless propaganda spread by the local police union and right-wing politicos; police statistics showed a 42 percent jump in property crimes by the non-homeless against the homeless over the previous year. Starting in November, the governor ordered disruptive weekly clearouts of camps in underpasses.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the state cleanups have halted and so have the governor’s tweets. But the backlash hasn’t ended: A group called Save Austin Now—a coalition including the Travis County Republican Party chair and the police union—spent five months gathering signatures for a November ballot initiative to restore the old ordinances. In July, the group submitted about 24,000 signatures, but the city clerk rejected the petition, saying too many of the signatures were invalid. Save Austin Now’s founders then announced a political action committee aimed at electing pro-criminalization city council members. In August, the Austin suburb of Leander passed its own camping ban, and the governor has also promised a state legislative response when the Legislature convenes next year.

Chris Harris, director of the criminal justice program at Texas Appleseed, an Austin-based nonprofit, pushed the 2019 ordinance revisions and says that while he was surprised by the scope of the backlash, he always knew the reforms wouldn’t go down easy. “I think a change like this strikes at the heart of the grand bargain of many cities,” he says, “as it relates to city leadership, the business community, and the police.”

The history of Austin’s anti-homeless policies reveals the nature of that “bargain”—in which the moneyed can turn to cops to exclude the unhoused from desirable public spaces—and why most cities are reluctant to upset it.

The modern homelessness crisis is roughly as old as the arcade game Pac-Man. Before the 1980s, in the decades following the New Deal, homelessness was rare and largely isolated to older men in skid row districts of major cities. In his chronicle of American homelessness, historian Kenneth Kusmer says homelessness in the decades following World War II was less common than at any time since the mid-18th century. What changed that wasn’t a sudden upsurge in substance abuse or irresponsibility; it was a brutal confluence of economic trends, the destruction of cheap housing, and Reagan-era austerity.

In the 1970s, a global recession accelerated deindustrialization in America, shunting many high-wage manufacturing workers into unemployment and poverty. If there was cheap housing to catch them, it was rapidly disappearing. Nixon had frozen federal subsidized housing programs, and a national gentrification program known as “urban renewal” was destroying affordable urban housing around the country, including in the skid row districts. When Reagan took office, he slammed the pedal to the floor by kicking hundreds of thousands off federal disability benefits and gutting public housing and Section 8 voucher budgets. An older generation of the concealed homeless merged with a flood of the newly unhoused and washed out onto the streets of American cities.

Texas’ capital, though less than half its current size, was no exception. During the 1980s, Austinites saw their unhoused population grow into the thousands; the city formed its first homeless task force in 1985, and the Salvation Army built a downtown shelter in 1987. Unhoused activists, calling themselves the Street People’s Advisory Council, protested city leaders, helping push them to allocate a few hundred thousand dollars for services and housing. But such minor responses—paired with anemic federal action focused on funding temporary shelter through FEMA—did little to address the root causes. The crisis continued unabated.

In the 1990s, Austin’s homeless ran up against another nationwide trend: downtown revitalization. After three decades of disinvestment, developers and investors wanted the central business districts back—and the unhoused were in the way. “It was intolerable,” says Jose E. Martinez, the original director of the downtown business lobby group, the Downtown Austin Alliance (DAA). “The homeless would go and spread out cardboard and blankets and urinate and defecate on [businesses’] front doors. … The homeless would sleep on the benches, on the streets; throughout the day, they were out begging and demanding handouts.”

So Martinez, a former city planner, and his allies moved to take control of public space. In 1993, they won approval for a business improvement district, a special taxing area through which businesses can fund lobbying and private security. The money launched the DAA with Martinez at the helm, and in 1994, he started a “clean and safe” initiative. The hallmark feature was the Downtown Austin Rangers, essentially a group of roving cyclists supervised by the police who monitored the homeless and called the cops on them. They were “the ears and eyes for the police department,” Martinez says. The DAA also began lobbying for a citywide camping ban.

At the time, homeless suppression had become all the rage. In 1994, Dallas evicted dozens of residents from a shantytown under I-45 and cracked down on sleepers at City Hall, the convention center, and the downtown public library. Two years earlier, Houston had passed a law requiring panhandlers to stay 8 feet away from potential benefactors. One report identified 49 U.S. cities that either passed anti-homeless ordinances or cleared out camps in 1994 alone.

One group behind these policies was the American Alliance for Rights and Responsibilities (AARR), a right-wing nonprofit founded in 1989. According to Rob Teir, a Houston-based lawyer who was AARR’s general counsel, the group helped Dallas craft its crackdown and defended the city when it was sued over the camp clearout. Teir says the nonprofit also consulted with Houston business leaders and wrote a camping ban in Santa Ana, California, which inspired Austin’s ban. The group was partly the brainchild of John Tanton, a white nationalist often deemed the architect of the modern anti-immigrant movement. In a 1989 interview, Tanton described the organization as a means to combat a supposed surge in “brand-new constitutional ‘rights.’” AARR’s first director, Roger Conner, had previously led Tanton’s anti-immigrant group, the Federation for American Immigration Reform.

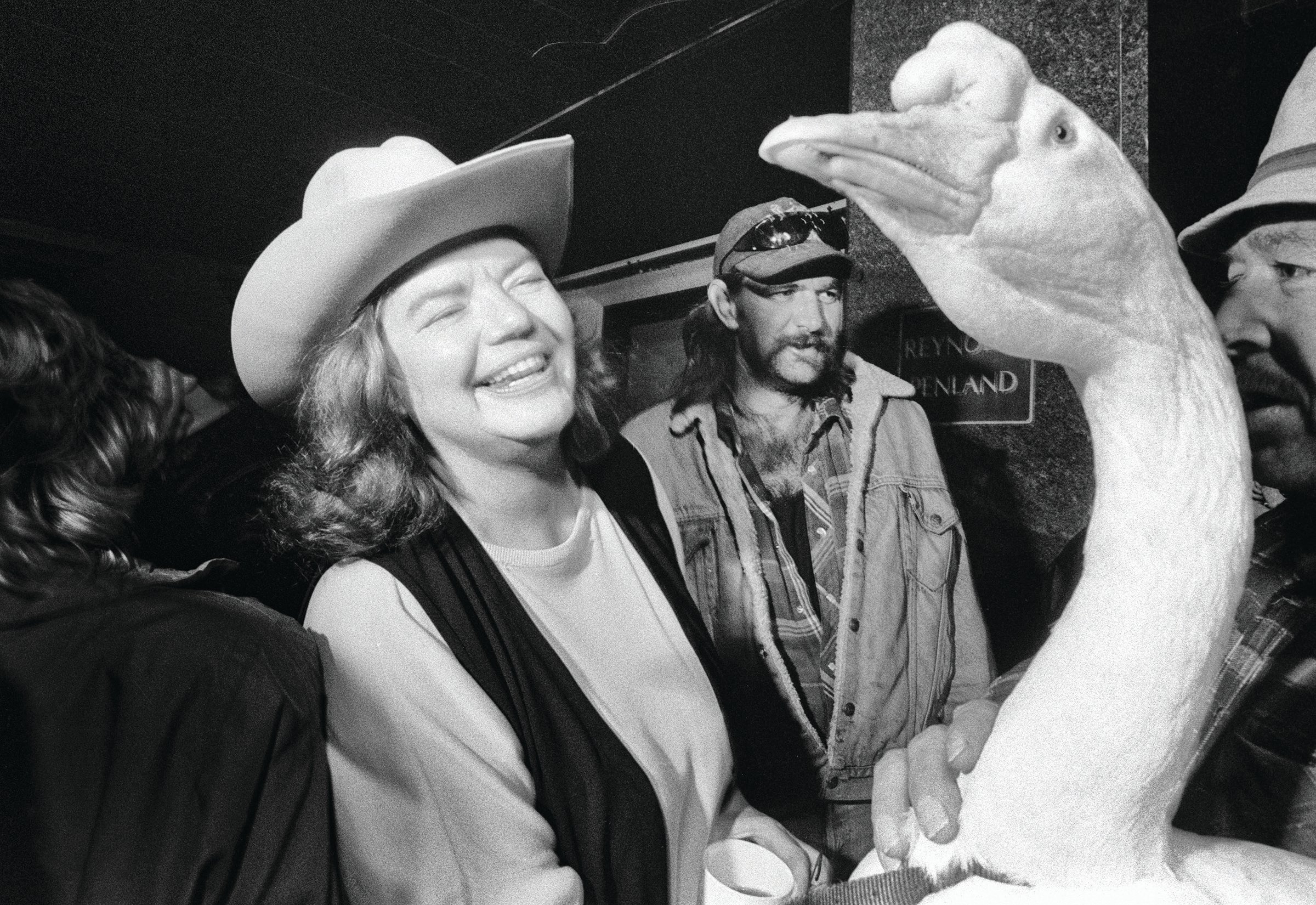

In liberal Austin, many residents balked at the proposal to ban camping. The Austin American-Statesman was flooded with letters opposing the proposal. “Trespassing on private property already is a crime; every place is either public property or private property, and a law higher than that of city ordinances requires human beings to sleep,” wrote Laurence Eighner, who published a bestselling memoir of homelessness in Austin in 1993. When the ban passed on first reading in July 1995, the council was “met with hisses and shouts from some of the 125 homeless people and their advocates in the audience,” the Statesman reported. Still, in January 1996, the measure became law by a single vote—prompting former Texas Observer editor Molly Ivins to spend a night in a sleeping bag on Congress Avenue in protest.

Within a year, the city council was on the verge of repealing the ordinance. More than 2,000 citations had been issued, but almost no one showed up to court, and all the city had done was shuffle the unhoused around. The policy had “succeeded in moving public camping farther out of sight from the business areas, but the problem has resurfaced in residential neighborhoods … [and] deep within brush and thickets,” reads a 1997 memo from staff to the city council. But the DAA fought to keep the ordinance and struck a deal with then-Mayor Kirk Watson and council members: Among other agreements, the camping ban would stay and the DAA would not oppose a new shelter downtown. (Seven years later, that shelter would become the Austin Resource Center for the Homeless.)

In the years following the camping ban, the DAA saw its dreams realized: Downtown transformed. The residential population more than tripled between 2000 and 2019, and real estate skyrocketed. “In the early ’90s, downtown office space rented for $10 a [square] foot less than anything out in the suburbs, and we turned that around, big time,” says Charlie Betts, who led the DAA between 1997 and 2015. Longtime Austinites may recall this period, alternately, as the city’s coming-of-age as a tech capital, the death of its “weird” free-spiritedness, or the exodus of many Black Austinites. Regardless, business interests viewed hiding the homeless as part of the project. In 2001, at the DAA’s urging, the city added the restrictions on panhandling and sitting or lying down in public. “We wanted people to office downtown, live downtown; we wanted them to feel safe,” says Betts. “And the ‘public order’ ordinances were a part of that.”

Meanwhile, Austin’s unhoused were racking up tickets and warrants. Records obtained by the Observer show that between January 2000 and May 2020, nearly 53,000 citations were issued under the ordinances—75 percent of which turned into warrants. The municipal court would not provide data for years prior to 2000. The records show a spike between 2013 and 2015, a period accounting for some 24,000 citations. In summer 2018, when the city council first suggested it would repeal the rules, enforcement fell sharply. And since last June, when the ordinances were revised, tickets have slowed to a trickle: Only 125 have been issued through May, with 34 percent becoming warrants.

Many defenders of the ordinances describe them as innocuous. “They’ve never been enforced very strictly,” says Betts, who supports the bans and thinks the city made a mistake in changing them. “It’s never to my knowledge been abusive.” Police describe the laws as just another “tool” in their public safety kit.

But longtime homeless advocates say the ordinances had dangerous consequences. Richard Troxell, who launched the nonprofit House the Homeless in 1989 and was once homeless himself, founded a yearly memorial event in Austin to recognize what he calls “an endless stream of people dying on our streets” in part due to the camping ban. “They call the ordinances ‘one more tool in the toolbox’—well, no shit, a tool to repress people that don’t have the money and comfort you have,” he says. “It’s a weapon.”

Valerie Romness recalls the bans being enforced in waves, including to run folks out of downtown before music festivals or away from the University of Texas campus before Mother’s Day. Romness, who runs the local homeless newspaper the Challenger and has worked with Austin’s unhoused for 30 years, says that over the past two decades, people have been pushed south and then north to the underpasses where encampments are seen today. But new homeless never stopped coming down the pike, filling places abandoned by others. “Twenty-three years we wasted money on the camping ban; it could’ve been spent toward housing,” she says.

That’s the goal of the D.C.-based National Homelessness Law Center (NHLC). For 31 years, the group has sued cities around the country to overturn laws targeting the unhoused. It’s had some wins, including a 2015 Supreme Court ruling that undermined panhandling bans nationwide (meaning Austin could be ripe for a lawsuit if its law were restored). Last year, the Supreme Court also let stand a ruling that blocks localities in Western states from enforcing camping bans when insufficient shelter space exists.

For NHLC, the lawsuits’ aim is to convince governments to redirect funding away from the criminal justice system and toward housing. “The goal is not to protect the right to sleep on the street; the goal is to make leaders stop using these laws as a crutch to avoid the harder decisions about housing,” says Eric Tars, the center’s legal director. That’s what Austin tried to do. Now comes the hard part.

A year after Austin’s ordinance changes, the city hasn’t significantly reduced homelessness. In January, this year’s point-in-time (PIT) count, a federally mandated tally of the unhoused on a given night, indicated an 11 percent jump over the previous year. Just drive around the city and you’ll see new camps on medians and in front of a library near downtown. A state-sanctioned camp in Southeast Austin—set up last year by the governor in a perplexing attempt to rebuke the city council—hosts more than 100 campers, as of July, despite its remote location and lack of protection from the scalding Texas sun.

But there’s another way to view these developments. During the PIT count, the unsheltered homeless were easier to find because they weren’t hiding, and there were nearly 40 percent more volunteers out looking than in 2019, a result of the political attention. “We counted more of an already existing population,” says Matthew Mollica, director of the Ending Community Homelessness Coalition, the city’s lead homelessness agency. Austin is in the process of buying multiple hotels to house homeless people. And since the onset of COVID, the city finally provided hand-washing stations and port-a-potties to encampments. Mollica thinks revising the laws was essential for pandemic-related outreach. “I think we definitely saved some lives with the ordinance changes.”

Harris, the Texas Appleseed advocate, notes the resonance of last year’s efforts with this summer’s mass uprisings against racist police violence. “Our campaign was saying, ‘We don’t think police help with homelessness; they hurt.’ And now we have a national focus on the same thing, but broader,” he says. In August, Austin cut more than $20 million from its police budget, with more cuts potentially on the way, and Harris thinks decriminalizing homelessness helped pave the runway for that reform. In Travis County, 36 percent of the homeless population is Black compared to 9 percent of the general population, a trend reflected nationwide.

So far, no other Texas city seems eager to follow Austin’s lead on homeless decriminalization—though there’s good reason for them to question their own policies.

Records obtained by the Observer show that Dallas, which maintains a ban on sleeping in public, has issued more than 38,000 sleeping citations since 1998, with more than half resulting in warrants. Ticketing has continued through the pandemic. Dallas also restricts panhandling and, in 2016, re-created 1994 by clearing out a massive encampment under I-45. Houston, meanwhile, bans sitting or lying down during the day in designated areas, which the city has been expanding from downtown to more neighborhoods for 18 years. Since 2007, the Bayou City has issued nearly 25,000 citations for sitting and lying—on top of enforcing bans on camping, panhandling, and restrictions on sharing food with the homeless. San Antonio also maintains a set of anti-homeless laws, including a ban on “soliciting from occupants of vehicles” that’s led to 35,000 citations and 11,000 warrants since 2001.

Greg Casar, the Austin City Council member who led the ordinance rewrites, says the backlash in Austin may have deterred other cities from considering similar changes. Maybe, he says, they’ll wait to see if Austin can tame the politics of the issue by actually housing the homeless. Like the rest of the council, he hopes business interests and the city can row in the same direction by pursuing “housing first,” the philosophy that permanent affordable housing is the solution to homelessness.

And there might be daylight. Bill Brice, one of the DAA’s current vice presidents, wishes the ordinances had remained stricter than they are now, saying visible homelessness is “bad for business and bad for tourism,” but he stops shy of calling for a return to the old ways. “The focus needs to be on how we address homelessness, how we address poverty,” Brice says. “If we don’t get there, we can write or rewrite all the ordinances we want and it won’t solve the problem.”

It won’t be easy. Tied with Las Vegas, Austin today has the fewest affordable housing units available to the extremely poor of any city in the country, with just 14 places to live for every 100 people. Even the city’s fast-growing economy can’t keep pace: Rent has outpaced renters’ income by 5 percent since 2008.

Then, there’s the looming eviction crisis triggered by COVID-19. Based on unemployment, a researcher at Columbia University predicts a possible 45 percent jump in homelessness nationwide by year’s end. With millions missing rent and eviction protections either expiring or being unevenly enforced, the remote goal of ending homelessness could become even more distant. But Casar insists Austin made the right move, no matter what the future holds, by affirming the “basic civil rights” of the unhoused.

In Austin, we’ve seen that visible homelessness can spark a backlash. But Steven Potter, a 53-year-old filmmaker who’s unhoused and serves on the city’s Homelessness Advisory Council, thinks the current economic troubles will sow empathy for the unhoused. “In the aftermath of these COVID shutdowns, people are going to be more understanding,” he says.

Perhaps, Potter hopes, today’s crisis will make more of us realize just how close we are to learning the true value of a tent, or the danger of a creek bed.